The photobook that took me a year to fully understand.

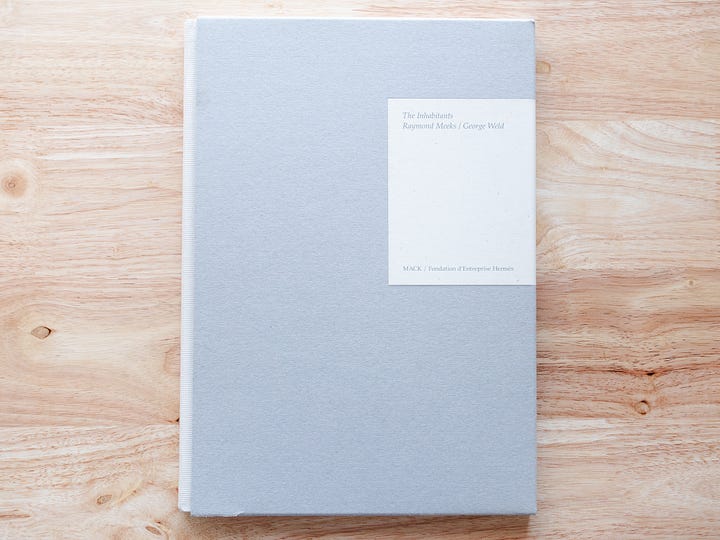

The Inhabitants by Raymond Meeks and George Weld.

First water, then land. First darkness, then light. Breath into human form, breath into voice, breath into song. Void into form. Place out of no-place.

Inarticulate, frozen at the joints.

The hunger for meaning deforms everything.

We are emerging from beneath the earth, slouched and hunched over, avoiding the light as we work towards it, fractured, trying to make sense of no sense.

This is where the story begins in Raymond Meek and George Weld’s “The Inhabitants,” published by MACK and the Fondation d’Entreprise Hermes.

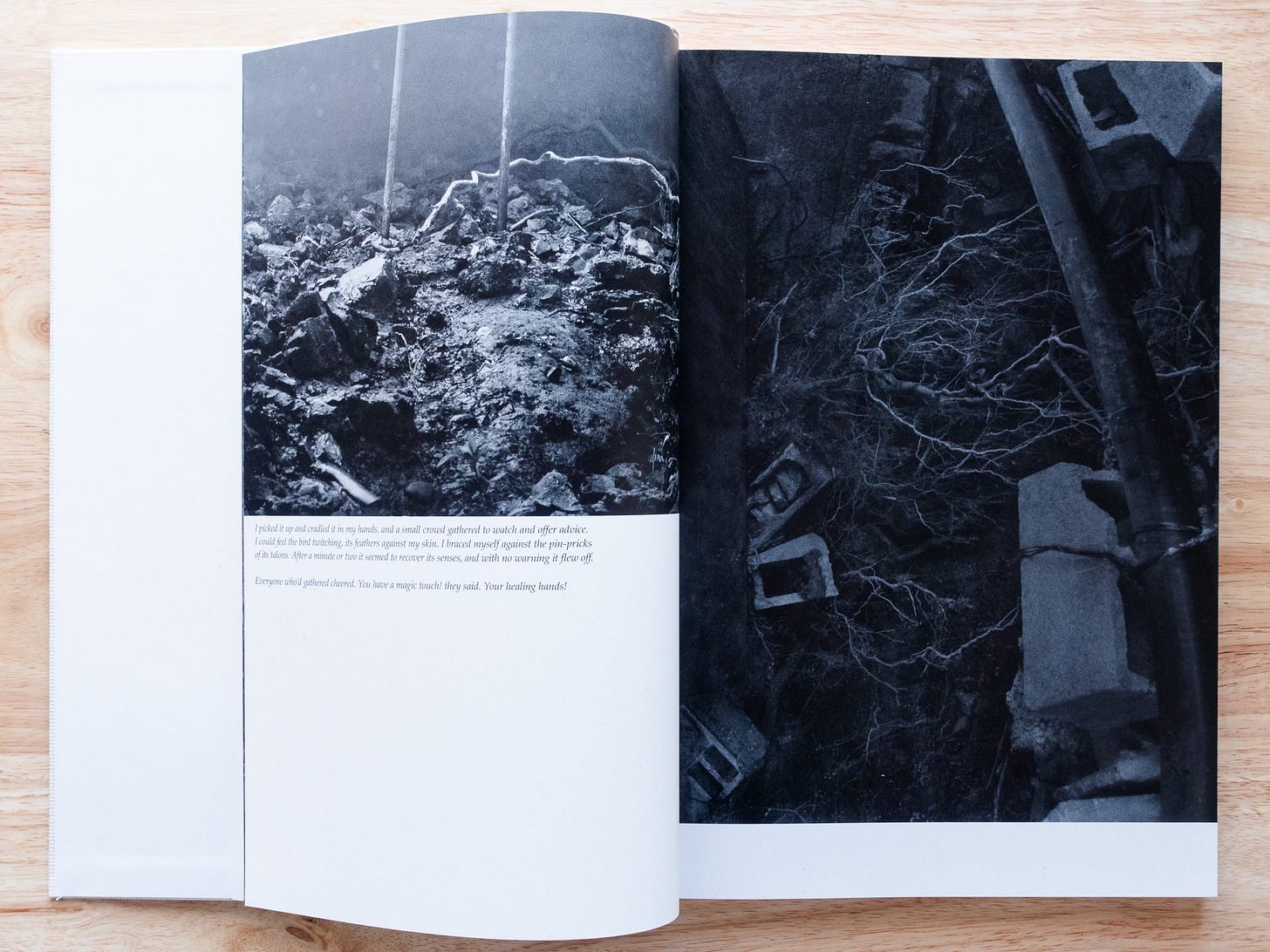

Like the opening credits of a film that hint at what's to come, the first four spreads of The Inhabitants perfectly outline what is to come in this book through the fragmented pieces of a whole image spread across three pages with Weld’s text before reaching form on the fourth spread, only to be echoed by another fragmentary arrangement of detritus.

A word on a slate, written in chalk, chalk wiped clean with a rag. A slate on a wall, hung by a wire.

I stammer. I hem and haw. I speak with a voice as clear as a bell, words flowing like a river. My tongue is tied in knots. I look about helplessly, powerless to speak. I stand and the column of air rises from my diaphragm to my mouth, quivering with meaning, enlivened by a thought that shaped it.

An unexpected trill. A murmuration.

I picked it up and cradled it in my hands, and a small crowd gathered to watch and offer advice. I could feel the bird twitching, its feathers against my skin. I braced myself against the pin-pricks of its talons. After a minute or two it seemed to recover its senses, and with no warning it flew off.

Everyone who’d gathered cheered. You have a magic touch! they said. Your healing hands!

The Inhabitants is a book that requires the synthesis between image and text to exist.

Though words and pictures live parallel to each other, and one does not dictate the other or influence the reading of each other, they breathe equal life into the book as a whole.

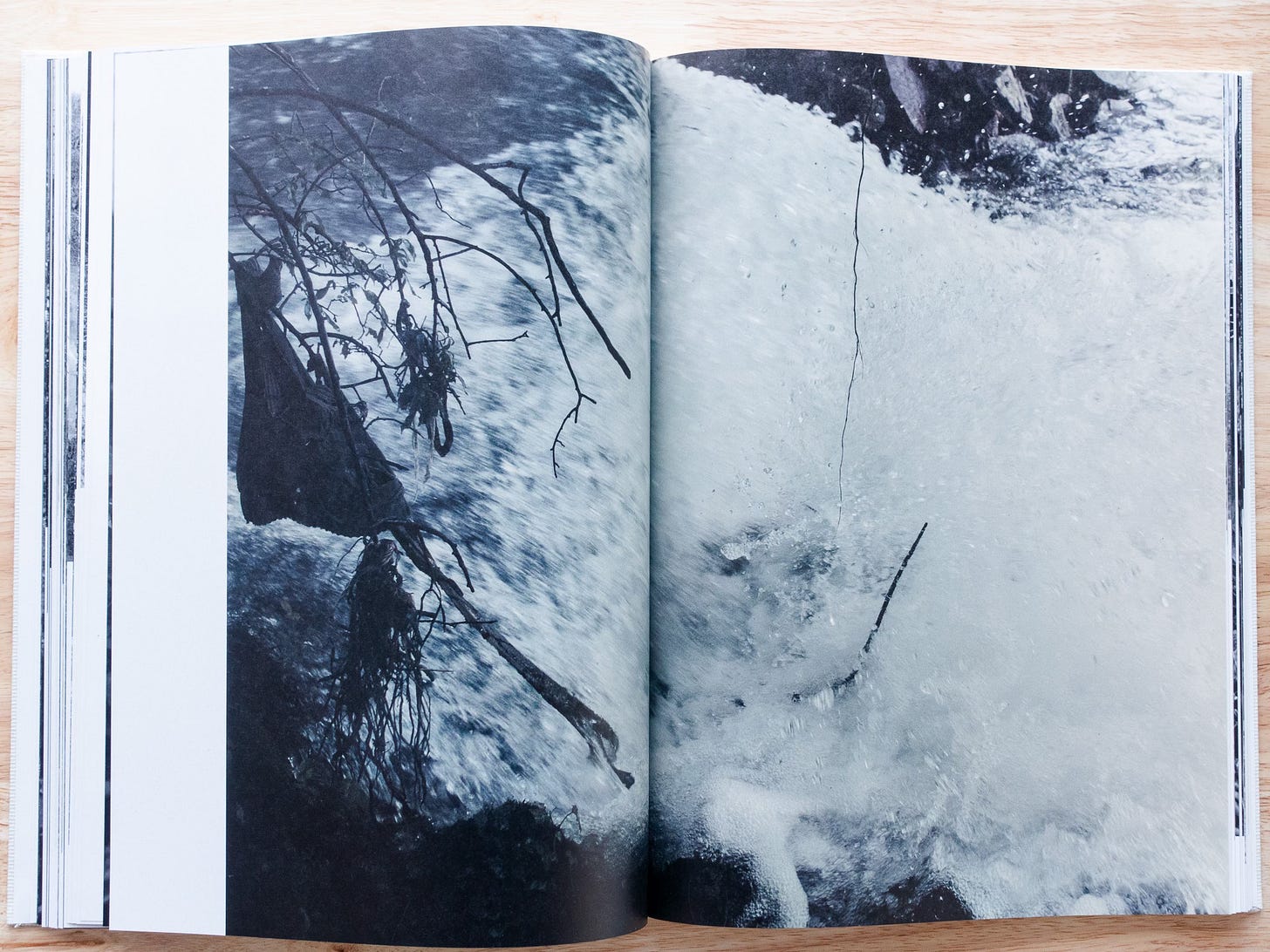

Turning the pages of this book feels like placing your hand on the back of a loved one and feeling their chest expand and deflate with every breath they take, text into image, image into text, no breath more critical than the other, every breath feeding the flow of movement through zones of migration in Calais, and the northern border between Spain and France.

We are moving unseen in areas that provide temporary shelter but no permanent rest to those migrating along the Bidassoa River, which separates France from Spain for several kilometres.

Though we meet no traveller in their physical form, we encounter them through the ephemeral bodies left behind by signs of brief inhabitation: footprints, lost shoes, string tied together in some structure, industrial and household detritus, cardboard boxes, markings, and holes in the ground that look like an archeological dig of some kind.

The book resists reduction by not including specifics about the crisis unfolding in the world Meek is photographing but leaves it open to the feelings of “what does it feel like to be unmoored, to feel unseen, not to feel as if you have a voice in the word?”

This lack of a transactional approach between the subject and the photographer is probably the book’s biggest strength and perhaps its biggest risk. However, I feel this book will long outlast itself and serve as a document about “being inhibited by a place, being inhabited by an experience or another person’s story,” so it is larger than the sum of its parts.

I loved to listen to the sounds of people speaking, the unarticulated flow of their speech, words neither beginning nor ending, just one long flow of molten language. I could imagine it to mean anything, almost anything.

Phrases of music, passages of speech: words that seem to become patterns, repeating rhythms or associations. A motif. An aria. An erratic, unexpected protrusion.

The writer George Weld never stepped foot in Calais, and he began writing for the book even before seeing the first images from Meek’s first visit to the region. Instead, he immersed himself in the area's history and the current crisis unfolding while Meek made images for the book.

The importance of his writing not responding to any particular image makes their synthesis complete and parallel. His fragmentary style (perhaps derived from whole texts) feels at home in a world where one could imagine finding pieces of broken text lying on the ground, written on a wall, stuffed away in a lost jacket pocket to be received by the new recipient with abstract meaning.

I was reduced to gesture, sound, an improvisation of my body, a desperate game of charades.

Imagine not being able to speak, or speaking but your words appearing in the air before you as nothing but line twisted into ornate and useless knots.

Both Meek’s and Weld’s sensitivity to the experience of being inhabited by displacement functions as a way for us to experience this untethered journey that requires us to keep our heads down, our language in our bodies, our feet in the river, and our hearts in the shadows.

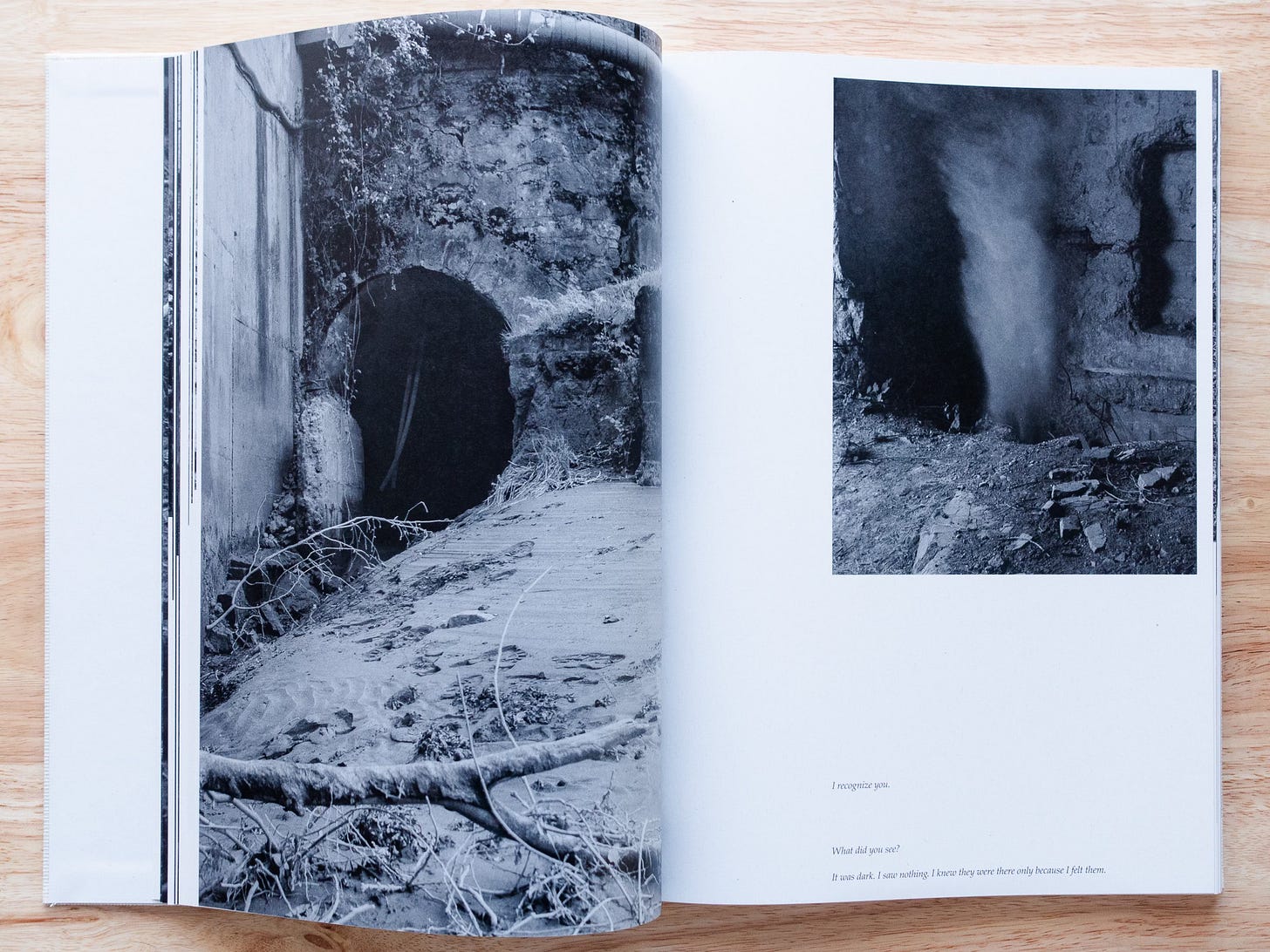

I recognize you.

What did you see?

It was dark. I saw nothing. I knew they were there only because I felt them.

All night I wait and watch. My eyes play tricks on me. I can’t always say what I’m seeing, if it’s a cluster of bodies moving in the shadows or a throbbing capillary deep in my eye, the effect’s the same, it looks like the dark is breathing. A third possibility: the dark itself is sentient, some part of it.

Meek is known to mix colour and black-and-white images in his books, and The Inhabitants is no different. The colour takes up very little of the work and arrives at precise moments with its heavily desaturated colours, reminiscent of Polaroid film without the built-in nostalgia.

A torrent of blue-tinted water would greet us with much reprieve if it weren’t for its raging pace as we look down into it while removing our shoes and cupping our hands together to dare take a moment of repose and contemplate our position in the world.

The boundary was marked by a river. The river knew no bounds.

In a live talk during episode #3 of “Le Feuilletage” hosted by Clément Chéroux, Raymond Meeks questions the idea of experiencing beauty by being in places where refugees and asylum seekers had crossed the Bidossoa River and “also wondering do they experience beauty the way I experience beauty, as somebody who has been forced into displacement.”

I believe this ties into the notion of George and Raymond attempting to be inhabited by this place, the displaced people sheltering and migrating there, and their stories and experiences.

The whole of the book feels crouched, hugging the river, seeking the shadows, sharing in whispers, reading in abstraction, wanting to be heard, to be seen, to stand upright in the light, but never doing so for the consequences of leaving the perceived safety of slouched shadows and muted voices.

At night I look into the sky and wish for it to come closer; even a single branch crossing my view has the effect of an embrace, something to hold me in place, to keep me from floating off into the depths of night.

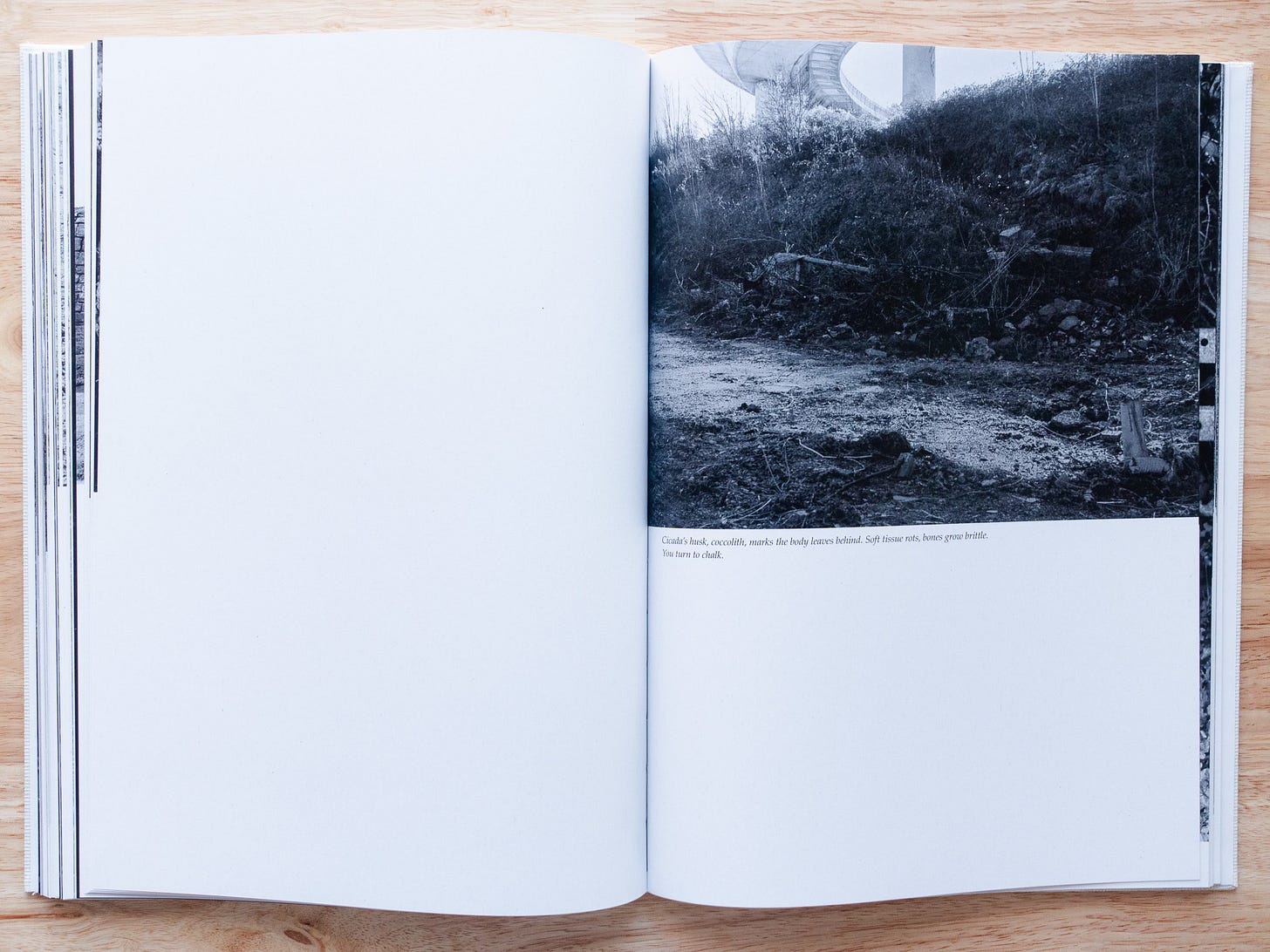

Cicada’s husk, coccolith, marks the body leaves behind. Soft tissue rots, bones grow brittle.

You turn to chalk.

I need to be seen to know I am real.

I need to stay out of sight.

They are looking for me.

They avert their eyes.

You can fit your body in this hallow like you were pulled from it at birth, like the theory of the continents drifting apart, don’t we all want to go back where we came from, curl into that shelter, that cove, that place where the land wraps around us like a cupped palm.

The Inhabitants is a powerfully restrained book, and it has taken me almost a year to digest it fully, so I feel slightly comfortable talking about it with all of you today.

I am far from an academic, and I will include other reviews, YouTube videos, and Podcasts in the footnotes of today’s newsletter to allow you to inform yourself about certain aspects of this book as you wish.

I receive things emotionally, and this book is heavy yet full of beauty.

Raymond Meeks and George Weld created a beautiful object with a minimal feel, inelegant materials, recycled paper, and a rough cloth that wraps the book, all of which invoke the experience and inhabitation found within its pages.

If you can still find a copy, I highly recommend it. However, be prepared to invest in this book; it takes many readings to fully appreciate its value. This is no easy read, and nor should it be.

I brought your language back to you.

Thank you for stopping by today. I plan on making more of these personal reviews of photobooks from my collection as I feel like writing about them.

The Inhabitants has been on my mind since I picked it up last spring. After sitting with it and reading what others had to say about their experiences, I felt like I could finally articulate some helpful thoughts or commentary on it.

Take care of yourselves, and I’ll see you all next time.

I should also mention that all pulled quotes throughout today’s newsletter are from George Weld’s text in The Inhabitants, either as they are presented in the book to their placement on the page to the images or rearranged by me to fit the flow of my review (hopefully not to the horror of George and Raymond), and all quotes within the text body of my review are taken from Raymond Meeks when speaking about the book with George and Clement at Le Feuilletage in France.

What a lovely review, man. Good stuff!

Wow, this sounds and looks incredible. Thank you for your introduction to this book!